Or at least put it on a diet?

Considerations on Managing the capital invested in your business

A long-time board member for a family business I know regularly remarks that the family should “not starve the goose that lays the golden eggs.” Beyond being an entertaining metaphor, this director’s remark has the added benefit of sounding quite wise. It is easy to conjure up scenarios of when the family’s demand for dividends is so large that it prevents the business from being able to invest for growth as it should.

The sentiment also occurs similarly business owners who do not want to invest outside of their core operating business. Their opinion is typically phrased something like this, “I’m getting 20% returns on every dollar I invest in my business, so why would I invest in public markets / private equity that is going to give me a lower return?”

These two views – not starving the golden goose nor investing in lower return projects – can work in parallel to lead business owners and their families to be over-invested in their core business. As the saying goes, the best way to build a fortune is concentration and leverage.

But don’t forget the best way to lose a fortune – also concentration and leverage.

For the remainder of this post then, I want to explore when and why a business owner might choose to go a different path. Said differently, when should the golden goose go on a diet? There are two primary perspectives to consider in answering such a question. The first is to look internally at the business itself. The second is an external focus on the broader investment environment.

First – the internal view. Any business owner (or group of owners) should develop a robust and articulated philosophy regarding capital investment in the business. Often, ownership groups really like the core technology of their industry and as a result may easily spend too much on capex. If you like buying capital equipment, odds are you are probably going to buy a lot of it. For example, a local small business near my office has a fleet of vehicles that is mind blowing every time you drive past the lot – especially considering the size of the business.

To develop this philosophy on capital investment for your company, it is helpful then to consider what are reasonable rates of reinvestment within your core operating industry. Here I’ll tip the hat to the team at Mercer Capital. Their annual benchmarking guide has some great analysis about how family businesses manage their capital across a wide group of industries.

Thoughtful owners should know what % of cashflows their peers are re-investing in their businesses. And in the same way, the owner should be carefully monitoring their capital spend to determine whether they are generating the expected rates of return.

These returns should be compared against something to make sure that the juice is worth the squeeze. Question for owners to ask – have you defined your cost of capital? Every dollar that the family puts in / keeps in the business could be invested elsewhere at other rates of return. By setting a cost of capital, the business owner is saying this is the threshold level of return that I need to receive in order to receive returns appropriate for owning this business.

Once the returns on invested capital (ROIC) sink below the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), then the dollars invested are not actually adding value.

That’s the internal side of the ticket, let’s consider next the external view – the broader investment market?

If you are not going to reinvest in your business at a rate of return you know and control, when / where does it make sense to invest in other opportunities. Why might it make sense to invest in something with lower returns than your core business?

To understand this, we must consider a few dynamics of theory around portfolio management. So as highlighted above, concentration and leverage (either operating, financial, or both) are the only ways to generate a significant fortune. If you are too diversified, you will not have enough exposure to your highest return investments to generate an outsized return. Leverage (in line with Archimedes’ thinking on levers more generally) can magnify positive returns to stratospheric levels.

Yet once a fortune has been created – the game changes. If you have nothing to lose, it is easy to seek much greater risk. But once there is something to lose, the maxim is right, it is a great shame to have to make a second fortune.

Far too often, a business owner knows that they are receiving 15% returns in their business and faced with the chance to make 10% – will say it is not an attractive option. I heard this verbatim from a small-town Texas retailer I once had dinner with. Real estate investors are also notorious for this as well – why would I want to own anything other than Nashville real estate? The key here is that while the return portion of the analysis is important, the thinking is incomplete by considering it only in a vacuum.

As a business / wealth grows, the way the business owner thinks of themselves will need to evolve in a fundamental way. The business owner will need to take off their business manager hat (i.e. running the business decisions) and put on a portfolio manager hat. A portfolio manager hat looks at the business as an investment, separate from all the concerns and benefits that may go in to owning the business.

With the portfolio manager hat on, the business owner can now begin considering other additional dimensions. The first that should come to mind is considering what the actual risk is of owning a small capitalization corporation? While the owner may understand operating risks like raw materials prices or customer concentration. The risk of the business itself considers all these dimensions and specifically how they interact to affect the value of the business over time. This risk factor can be expressed in a volatility figure.

If the company is publicly traded, the volatility reflects how the stock moves up and down over time and the severity of those movements. But just because a privately held company does not have daily price volatility, does not mean that it is not exposed to similar risks. It just means that the owner is not aware of, and thereby not incorporating that risk into their thinking.

We discussed earlier how important it is for the owner to define a cost of capital. Far too often, this cost of capital only considers the returns of the business, and not its risk profile. This means that most owners meaningfully understate the cost of their equity capital.

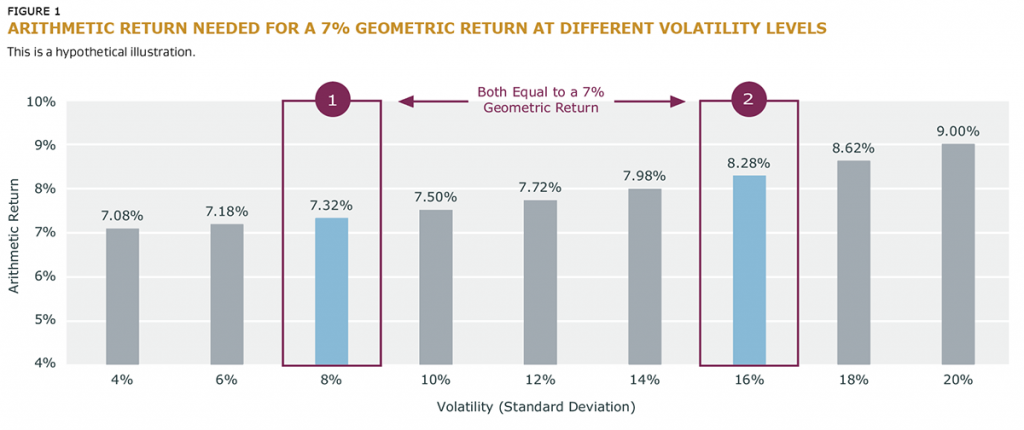

Only a well defined and appropriately specified cost of capital allows the business’s potential returns to be compared to other potential returns being offered by investment options across the global capital markets. With a broader perspective that incorporates both the return potential of the business, but also the risk profile of the business, the owner (as portfolio manager) can entertain a new consideration. Namely, that a lower return with less volatility, over a long-enough time horizon can generate returns equal or superior to something with higher returns but more volatility (i.e. risk).

Figure 1 – Volatility’s Impact on Returns

Source: https://www.intechinvestments.com/can-you-turn-investing-from-a-drag-to-a-delight/

Moreover, if assets with differing risk / return profiles have different levels of correlation, the net outcome is even better. Differing levels of correlation means that each asset experiences good and bad times on a timeline distinct from other investments. This process of blending assets is known as diversification. Diversification it has been said is the only free lunch in investing.

The Golden Goose Meets Jenny Craig

Because of ‘sunk costs’ (prior investments in the business) and most owners not looking to sell their business, additional investments into the business (like capital expenditures) are considered in a yes/no fashion, rather than weighed against other possible options to deploy capital.

The business owner with a long-term orientation needs to broaden their perspective to consider a sober assessment about the capital required to run their business and how that compares to peers. On top of that, an accurate assessment of the corresponding risks of the business and setting an appropriate hurdle rate (what rate of return the owner requires the business to earn) provide key inputs to evaluating broader investment options.

Often, a natural output of this thinking will be the creation of an investment program to capture investment returns that have different risk profiles and different correlations to the core business. By beginning to think like a portfolio manager, the business owner can potentially generate greater overall wealth, by lowering the risk of a portfolio with only a single asset. And moreover, limit the potential downside risk by having their wealth be more diversified. Said differently, feeding the golden goose the right amount (and no more) can allow an owner to have their cake and eat it too.

Disclaimer: Not Investment advice nor a recommendation to buy/sell any securities