We recently wrote about the nature of paradoxes in family enterprises. Paradoxes exist at the center of many family’s most central points of identity. How we ‘solve’ a paradox represents a family’s attempt to navigate the ambiguities of life.

One of the central paradoxes at play in families is the tension between tradition and change. For some families that have been functioning together for lengthy periods of time, centuries or longer in cases, traditions serve as powerful liturgies for the how the family promulgates its values and shares its stories with current and rising generations. For others, innovation and change harken back to the entrepreneurial heritage of the family. The ability to nimbly adapting to changing circumstances with new insight and new value creation can be powerful to the ethos of the family.

Families generally find they prefer one side of the ‘polarity’ created in each paradox – i.e. they default to favoring tradition or favoring change. Paradoxes are not static but take place in the context of a changing world. Said differently, managing a paradox is a bit like juggling – while the balls in the air are important (i.e. the paradox), the juggler stands on a surface which is subject to change as well. It is one of these “surface-level” changes that we want to consider which is having an outsize impact on families – namely accelerating rates of industry change.

The Reality of Change

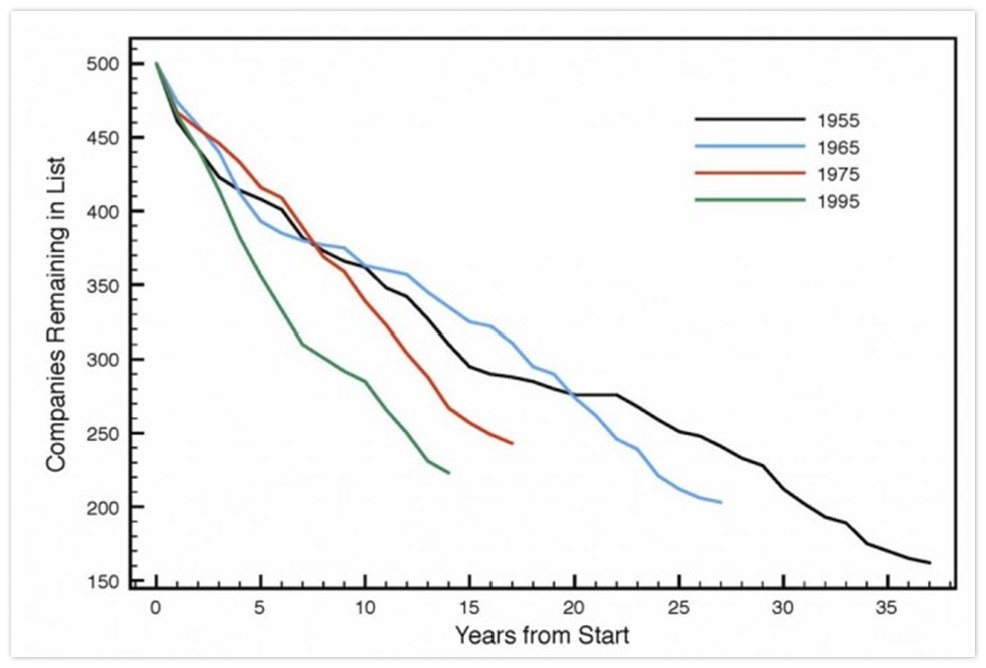

Figure 1 below is a favorite of mine. It shows different cohorts of companies that compromise the Fortune 500, and then plays forward how many remain in that list years later. As you can see the companies in the earliest groups remained in the list for longer periods of time. As we draw closer to contemporary days, the forces of creative destruction cut the 1995 cohort in half within 15 years vs. 30 years or more for the companies of the mid-1900s.

Even for the staidest of the 1955 group, only 12% were on the list in 2016. While this is not necessarily a perfect methodology as the Fortune 500 is a relative ranking based on revenues. Nevertheless, even if a company leaves the list but continues to exist, its inability to grow in line with the growth rates of new entrants speak to the maturity of the company and/or the industry in which it participates.

Figure 1 – Fortune 500 Turnover

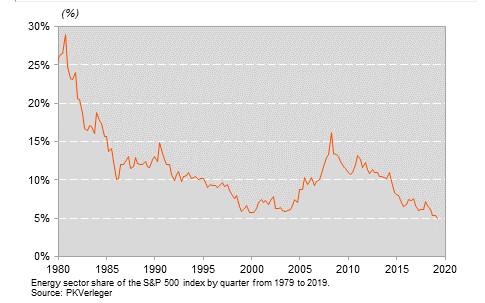

Consider the plight of the energy sector as well. Despite much of the world’s demand for energy still depending on fossil fuels, the economic prospects of the industry have fallen to such a level that after peaking at close to 30% of the S&P 500, the sector has fallen over 80% to now barely 5% of the value of the S&P 500.

Figure 2 – Energy as % of S&P 500

There are a few possible conclusions to draw from Figure 1 and Figure 2 but most salient in our mind is that no industry is immune for the forces of change present in the marketplace to do.

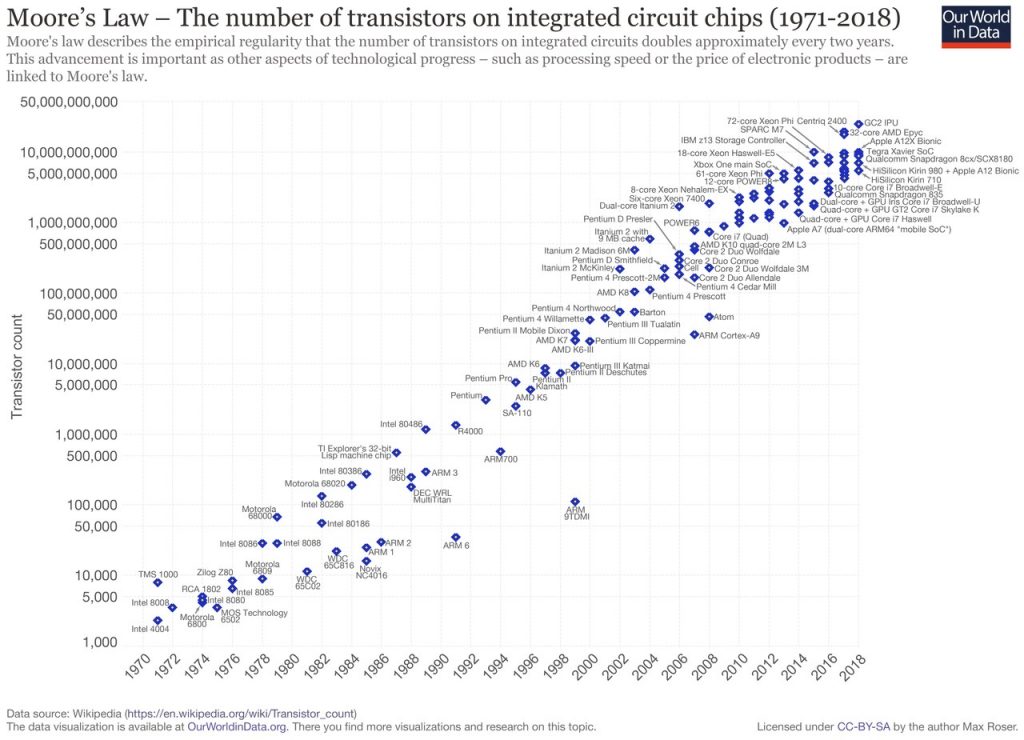

These forces, which economist Joseph Schumpeter, referred to as “Creative Destruction,” have been enabled by the miracle of processing power in recent years. Moore’s law, which theorizes that the number of transistors on a chip will double every 2 years, has led to remarkable changes in the world as we know it.

Figure 3 – Moore’s Law

Knowing Moore’s law and acting on it are vastly different things. Our brains prefer processing things in a linear fashion, not exponential. Leaders of companies have an impossible time thinking at internet scale because forecasting exponential growth feels so nonsensical.

What this means for business owners and investors is a they must make a continual push to shift their thinking to adapt to this new reality. For many companies that are technology first, they exist in a world of zero marginal cost. Once the product is created, the profit of each additional customer can be staggering. Or consider Facebook for example which introduced a new product, Stories, and was able to massively increase the amount of ‘space’ available to serve advertising against – the only cost incurred to open a vast new marketplace was the fixed cost of their software developers.

So how does this relate to families?

A common refrain expressed by business owning families is a view that the family intends to hold the business indefinitely – i.e. the business as “heirloom asset.” The family may have held the specific business for many generations and aspires to do so for generations to come. And here the paradox we opened with comes to play. While the family may have such a view (i.e. continue the tradition of the family’s business), it must also keep an eye pointed forward and an ear to the ground for the change that is coming.

There is no doubt, all industries are being changed in this broader technological cycle – just as all businesses are affected in the short-run by COVID-19. A great danger for family businesses is that with a strong allegiance to tradition, they may miss the tectonic shifts that could negatively affect the business in the long run.

Treating a business like an heirloom is a risky proposition. Businesses exist in a dynamic marketplace. If the past or a feeling of emotional attachment too heavily shapes the family’s thinking, they simply may not see the wave that kills them. Andy Grove, the former CEO of Intel, said it best – Only the Paranoid Survive.

While a family may wish to honor its legacy for generations to come through owning and operating the same business – it must also carefully consider whether they are the right owner to steward the business into the future. Else they risk seeing the legacy of the family and its business damaged if they are unable to adapt to a changing marketplace.